To a highly literate and mechanized culture the movie appeared as a world of triumphant illusions and dreams that money could buy. It was at this moment of the movie that cubism occurred, and it has been described by E. H. Gombrich (Art and Illusion) as “the most radical attempt to stamp out ambiguity and to enforce one reading of the picture — that of a man-made construction, a colored canvas.” For cubism substitutes all facets of an object simultaneously for the “point of view” or facet of perspective illusion. Instead of the specialized illusion of the third dimension on canvas, cubism sets up an interplay of planes and contradiction or dramatic conflict of patterns, lights, textures that “drives home the message” by involvement. This is held by many to be an exercise in painting, not in illusion.

In other words, cubism, by giving the inside and outside, the top, bottom, back, and front and the rest, in two dimensions, drops the illusion of perspective in favor of instant sensory awareness of the whole. Cubism, by seizing on instant total awareness, suddenly announced that the medium is the message. Is it not evident that the moment that the sequence yields to the simultaneous, one is in

the world of the structure and of configuration? Is that not what has happened in physics as in painting, poetry, and in communication? Specialized segments of attention have shifted to total field, and we can now say, “The medium is the

message” quite naturally. Before the electric speed and total field, it was not obvious that that medium is the message. p 12

MM is a little too pushy with his pet phrase here, but it appears he is using his interpretation of the interplay of the mediums of film, painting (both abstract, and representative), and photography to point out the ways in which cubism in particular creates involvement with the viewer in ways that representative painting could not.

MM’s terms of “involvement” throughout UM are somewhat difficult to grasp. Later he creates the framework of “Hot” and “Cool” media to help explain this dynamic. Even then the theories don’t always appear to coalesce. Here in particular he describes film as a medium of involvement, whereas later he will describe it as a “Hot” medium, which by his own definition necessitates less viewer involvement. I’ll attempt to grapple with these inconsistencies later when his hot and cool theories come to the front.

It may be more instructive to look at the way photography and film images transformed the uses of painting from the period of about 1850 to 1950. As photography slowly replaces painting as a way by which to simply capture a scene with accuracy, the focus of painting necessarily becomes interested in what photography cannot capture, particularly, interior human experience. As cartoons and films then are able to capture interior feeling effectively, painting is further pushed to the margins of abstraction(first via cubism, then via abstract expressionism) One could argue that a switch happens here in which the “involvement” shifts from the viewer to artist. That is, whereas older paintings in various European schools invite us to luxuriate in their impressive detail, the works of American abstract expressionists ask us to accept painting as a singular expressive act.

In this respect, cubism feels reactionary to growing popularity of film. It attempts to meet films dynamic ability to move about in space and time by introducing simultaneous perspectives in space and time in a single image. Here I’m thinking of something like Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, which approaches something similar to the early film experiments of Muybridge.

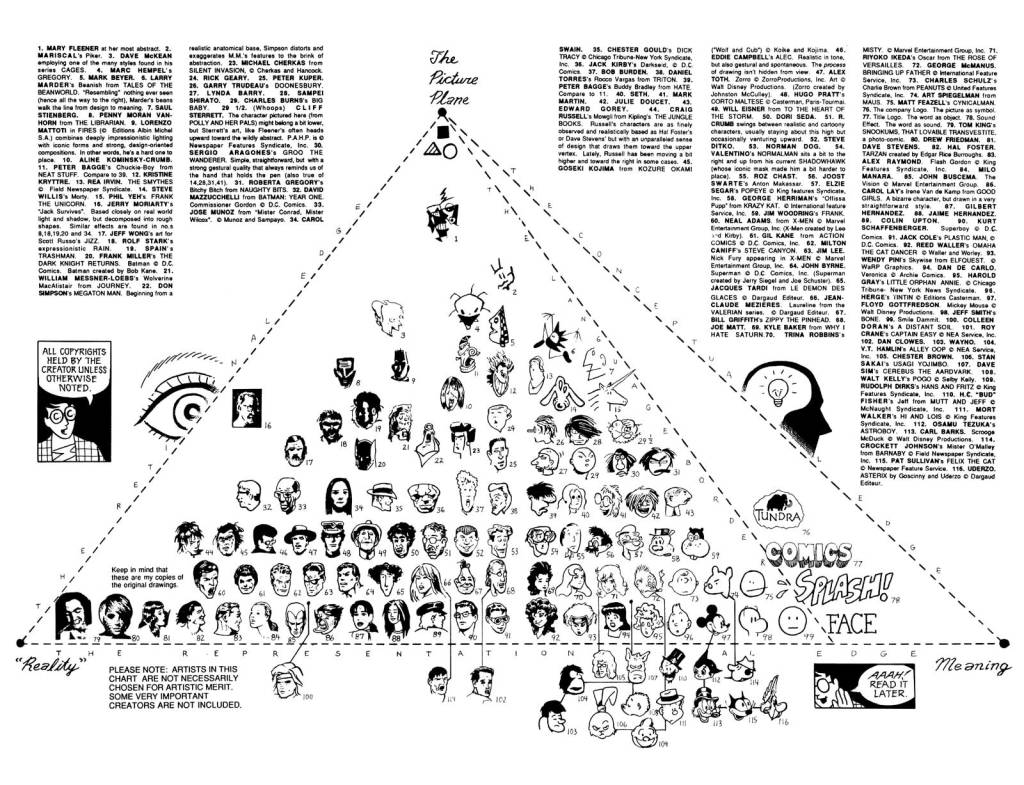

A handy framework for understanding the difference between the abstract and representative appears in a title that pays direct homage to Understanding Media, Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics. A good breakdown of which, with references to abstract art, appears here.

McCloud’s diagram introduces a third axis of “meaning” to those of representation and abstraction that further complicates the relationship between medium and message. The “representational edge” takes a face from a photograph to a word with a fairly smooth transition toward language representation, and stretches upward toward the abstract. Cubism seems to lie somewhere toward the center of the triangle, a moment in the history of painting caught between three simultaneous impulses toward meaning, representation, and the beauty of pure forms.