-

The Waste Land at 100

One hundred years ago this month TS Eliot’s poem The Waste Land had its first US printing. This landmark poem, which among other lit from that time marks the advent of the modern era, both in literature and throughout the greater culture, is at this historical moment particularly relevant. A number of peculiar similarities mark the writing of The Waste Land and our own point in history, among them an era ending pandemic, the nadir of an economic system, and an emergent shift in values.

If the work of Eliot and his peers marked the entry into the modern period, that period was somewhat short lived, at least in its primacy as the dominant mode of thought. While in some sense we can claim to still embody the values of this period (which are broadly a belief in a progressive society made possible by science, medicine, and collective action), that mode went out of vogue in the 60s and 70s with the advent of post-modern thought. And while in many ways we are still living now in that post-modern era, as well as among the vestiges of the modern era, many believe that values of post-modern thought (which are broadly a denial of the beliefs of modernity and an acceptance of moral agnosticism, skepticism, ironic detachment, and so on) are in turn falling out of favor in a turn toward what some are calling a “metamodern” mode of thought a generational synthesis which recognizes the value of modernity’s reverence toward some greater progressive ideal, while maintaining the ironic posture of post-modernity.

A great in depth discussion of these shifts can be found in the following 8 video series (worth watching through it its conclusion):

What appears to me as so striking is how historically these shifts mark changes in the economic development of the United States, and just how cyclical this development has turned out to be, eventually turning, like a gear on a wheel, a full revolution in roughly a century. Or, so that is if indeed the critique put forth by metamodern theorists isn’t itself one predicated upon a cyclical narrative.

The progressive era of the US economy (roughly 1930-1980) rose from the ashes of the liberal era(roughly 1870 to 1930) and roughly correlates to the dominant age of Modernism. In turn the the neoliberal age of the US economy (roughly 1980 to Now?–depending on who you ask) correlates to the dominant age of Post-Modernism. Indeed many see post-modernism as an expression of the values of late (neoliberal) capitalism and not merely a correlation. If indeed the twenty-teens, and twenty-twenties are marking that shift a cycle emerges, while also a kind of Hegelian synthesis.

That is, if postmodern thought is indeed the practical antithesis of modern thought, which a good case is made for elsewhere including in the above video series, then it would follow, that we are due for a synthesis of these forms following the very convincing structure of history laid out by Hegel, Marx/Engels, etc. Indeed other correlations emerge from that 100 year period. Following the ravages of WWI and the Spanish Flu the excesses of the liberal era gain momentum during the roaring 20s. Likewise, the fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic has only exacerbated inequality in the US, but we have yet to embrace a broadly socialist program as existed during and beyond the interwar period.

-

UUM 014

A Passage to India by E. M. Forster is a dramatic study of the inability of oral and intuitive oriental culture to meet with the rational, visual European patterns of experience. “Rational,” of course, has for the West long meant “uniform and continuous and sequential.” In other words, we have confused reason with literacy, and rationalism with a single technology. Thus in the

electric age man seems to the conventional West to become irrational. In Forster’s novel the moment of truth and dislocation from the typographic trance of the West comes in the Marabar Caves. Adela Quested’s reasoning powers cannot cope with the total inclusive field of resonance that is India. After the Caves: “Life went on as usual, but had no consequences, that is to say, sounds

did not echo nor thought develop. Everything seemed cut off at its root and therefore infected with illusion.”A Passage to India (the phrase is from Whitman, who saw America headed Eastward) is a parable of Western man in the electric age, and is only incidentally related to Europe or the Orient. The ultimate conflict between sight and sound, between written and oral kinds of perception and organization of existence is upon us. Since understanding stops action, as Nietzsche observed, we can moderate the fierceness of this conflict by understanding the media that extend us and raise these wars within and without us.

Uniform and continuous and sequential–does not describe MM’s approach to making his point on the divide between print and oral cultures. While he has offered some reasoning and examples at this point, his own style could be said to be oral, perhaps even religious. That is, there does not seem, in his early chapter to be a concise, rational explanation of his thesis. Instead, it works almost as a sermon, with its faith clearly held by MM, and the sparks of that privately held belief occasionally flaring up in myriad literary references to make some holistic sense, like observing a 3 dimensional object from every possible angle to confirm its shape.

Historically speaking, MM and UM, while feeling prescient to us in the internet age are also very of the moment. The dislocation he describes through contact with eastern cultures is a major feature of the 1960s in which UM was published. Through contact with eastern cultures (and indeed contact with drugs) many of the most compelling thinkers of the time (Joseph Campbell, Alan Watts, and Terrence McKenna among them) come into their own, not to mention a wave of popular culture typified by the work of the Beatles, Jimmy Hendrix, and others. Its seems clear the burgeoning culture clash runs deeper than just olds vs youngs or hips vs squares.

At this moment, a kind of globalizing of consciousness is happening and this has as much to do with media as with anything. The ability of television media to transport the images and sounds from all corners of the earth into the American home naturally creates a globalized awareness that is otherwise impossible. That awareness creates global citizens who see the old imperial wars between nation-states as an anachronistic aberration.

I suppose the more pressing question then, is one observing the current political landscape and “moderating the fierceness” of our own conflict by understanding the how the current media are working on us. Many of my thoughts on this can be found here. Broadly, I think the re-tribalization that MM points to as a consequence of electronic media is what is happening. TV may have opened the American consciousness to the global scene, but the internet makes each global citizen an active participant in a way that necessitates allegiances, and every tribe has its own truth.

-

UUM 013

De Tocqueville, in earlier work on the French Revolution, had explained how it was the printed word that, achieving cultural saturation in the eighteenth century, had homogenized the French nation. Frenchmen were the same kind of people from north to south. The typographic principles of uniformity, continuity, and lineality had overlaid the complexities of ancient feudal and oral society. The Revolution was carried out by the new literati and lawyers.

This may be the first time in UM that MM connects the galvanizing force of literacy brought by print to the creation of republics. It is one of the farthest reaching statements in UM, and I think one of the strongest, in part, because its effects are easier to overlook. That is, we think of inventions of machines as a means by which we gain greater control over nature, and seldom consider the ways that we are in turn affected, which feels to me as the central lesson to be learned from UM, that is, to train yourself to consider the ways that any new invention or medium may affect patterns of thought, and thus patterns of language, and then patterns of social organization.

And it is only on those terms, standing aside from any structure or medium, that its principles and lines of force can be discerned. For any medium has the power of imposing its own assumption on the unwary. Prediction and control consist in avoiding this subliminal state of Narcissus trance. But the greatest aid to this end is simply in knowing that the spell can occur immediately upon contact, as in the first bars of a melody.

MM takes the challenge a step further here–saying not only do new mediums change patterns of thought in ways that can be hard to quantify, they do so with unconscious power. MM relates the phenomenon to a trance or a spell. Like a drug, contact with new mediums can blind us to the power they yield, and contact may be hard to avoid.

A few works of literature that come to mind here are China Meiville’s Embassytown, Chuck Palahniuk’s Lullaby, and even the American remake of the film “The Ring.” In The Ring, a viewer watches a short clip which features abstract film episodes and always a ring shaped form. They then find out they will soon die because they watched it. As such the The Ring works as a type of horror based on the danger of new media. The power of film media is such that we cant help but watch, but there is an unknown consequence in watching. Eventually a ghost emerges from the screen to claim the life of the viewer. The corruptive force of power also being the them of other ring based media such as Wagner’s Ring Cycle and Lord of the Rings.

Interestingly, The Ring features a haunted VHS tape, a trope that has become more popular since in a series like Netflix’s Archive 81 series. And it is true that as technologies grow older and unused, their cache as modes by which to tell uncanny stories becomes more pronounced. One such internet story BEN DROWNED features a haunted Nintendo 64 copy of The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask. Indeed an entire genre of horror games has sprung up which exploit the look and feel of 64 bit gaming. Why exactly this works is harder to pin down, but if we take MM’s “extensions” at face value, if we accept that our media is as a prosthetic, ever becoming a part of what we consider our “self”, the horror may in part be the terror of looking down at you have accepted as your arm, and finding a monstrosity there instead. If we extend the body out into the universe of objects in our orbit, we thus extend our capacity for body-horror–avatars in gaming being one such extension.

Palahniuk’s Lullaby is a more straightforward correlation with MM use of “a melody” as a kind of siren song leading doomed media consumers to dangerous shores. In his novel, the protagonist learns a “culling song” a song that will kill a person just by hearing it. A similar tension ensues between the alure of power of using the song and need for destroying its power. Additionally, being a melody, it is infectious by design.

One of my favorite uses of media as narcotic takes place in Meiville’s Embassytown. An alien race at the edges of star system has evolved language in such a way that they are incapable of lying, indeed they are hardly capable of metaphor or simile, only of language that directly represents their reality. Because they form language by speaking from two mouths at once, ambassadors to this race are specifically genetically bred twins who are able to converse with them. A turning point happens when a non-ambassdor becomes able to speak the language. The effect of this two-fold voice on others in the race is immediately narcotic, so much so that the race is devastated by a stupor that comes over their entire civilization, where they need to hear the voice even to survive.

By speculating a language by which major upheaval of culture come through the unconscious affects of changes in media Embassytown is a rare narrativization of the effects of media on language.

-

UUM 012

To a highly literate and mechanized culture the movie appeared as a world of triumphant illusions and dreams that money could buy. It was at this moment of the movie that cubism occurred, and it has been described by E. H. Gombrich (Art and Illusion) as “the most radical attempt to stamp out ambiguity and to enforce one reading of the picture — that of a man-made construction, a colored canvas.” For cubism substitutes all facets of an object simultaneously for the “point of view” or facet of perspective illusion. Instead of the specialized illusion of the third dimension on canvas, cubism sets up an interplay of planes and contradiction or dramatic conflict of patterns, lights, textures that “drives home the message” by involvement. This is held by many to be an exercise in painting, not in illusion.

In other words, cubism, by giving the inside and outside, the top, bottom, back, and front and the rest, in two dimensions, drops the illusion of perspective in favor of instant sensory awareness of the whole. Cubism, by seizing on instant total awareness, suddenly announced that the medium is the message. Is it not evident that the moment that the sequence yields to the simultaneous, one is in

the world of the structure and of configuration? Is that not what has happened in physics as in painting, poetry, and in communication? Specialized segments of attention have shifted to total field, and we can now say, “The medium is the

message” quite naturally. Before the electric speed and total field, it was not obvious that that medium is the message. p 12MM is a little too pushy with his pet phrase here, but it appears he is using his interpretation of the interplay of the mediums of film, painting (both abstract, and representative), and photography to point out the ways in which cubism in particular creates involvement with the viewer in ways that representative painting could not.

MM’s terms of “involvement” throughout UM are somewhat difficult to grasp. Later he creates the framework of “Hot” and “Cool” media to help explain this dynamic. Even then the theories don’t always appear to coalesce. Here in particular he describes film as a medium of involvement, whereas later he will describe it as a “Hot” medium, which by his own definition necessitates less viewer involvement. I’ll attempt to grapple with these inconsistencies later when his hot and cool theories come to the front.

It may be more instructive to look at the way photography and film images transformed the uses of painting from the period of about 1850 to 1950. As photography slowly replaces painting as a way by which to simply capture a scene with accuracy, the focus of painting necessarily becomes interested in what photography cannot capture, particularly, interior human experience. As cartoons and films then are able to capture interior feeling effectively, painting is further pushed to the margins of abstraction(first via cubism, then via abstract expressionism) One could argue that a switch happens here in which the “involvement” shifts from the viewer to artist. That is, whereas older paintings in various European schools invite us to luxuriate in their impressive detail, the works of American abstract expressionists ask us to accept painting as a singular expressive act.

In this respect, cubism feels reactionary to growing popularity of film. It attempts to meet films dynamic ability to move about in space and time by introducing simultaneous perspectives in space and time in a single image. Here I’m thinking of something like Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, which approaches something similar to the early film experiments of Muybridge.

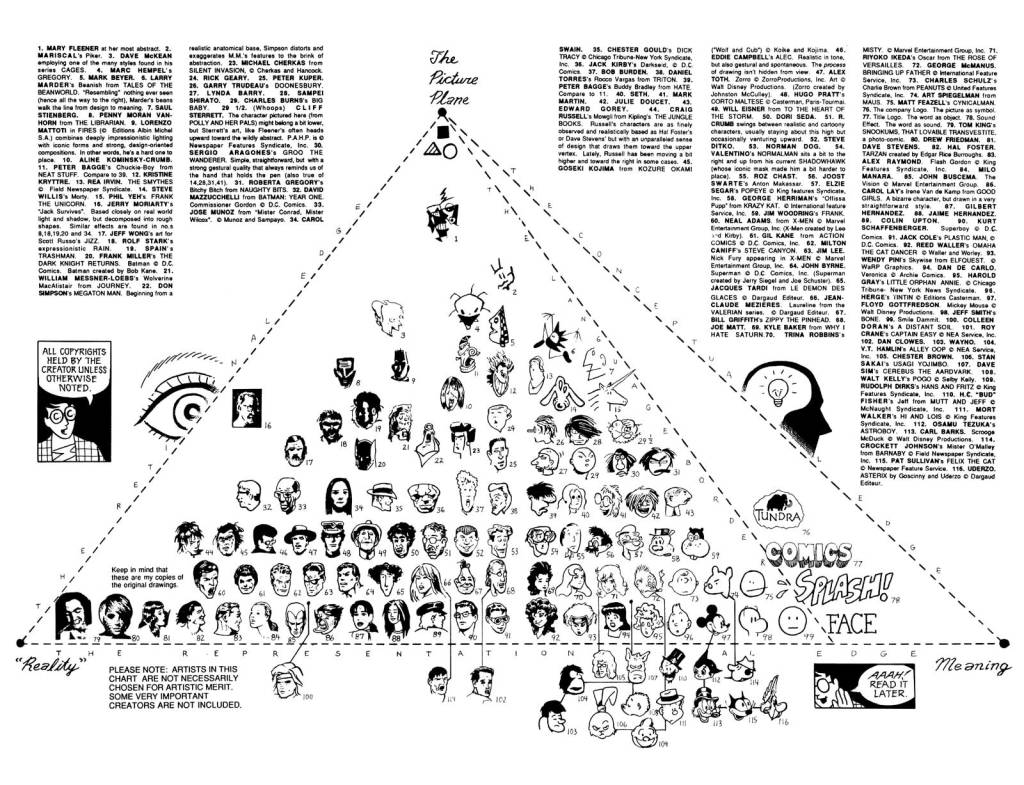

A handy framework for understanding the difference between the abstract and representative appears in a title that pays direct homage to Understanding Media, Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics. A good breakdown of which, with references to abstract art, appears here.

McCloud’s diagram introduces a third axis of “meaning” to those of representation and abstraction that further complicates the relationship between medium and message. The “representational edge” takes a face from a photograph to a word with a fairly smooth transition toward language representation, and stretches upward toward the abstract. Cubism seems to lie somewhere toward the center of the triangle, a moment in the history of painting caught between three simultaneous impulses toward meaning, representation, and the beauty of pure forms.

-

UUM 011

Just before an airplane breaks the sound barrier, sound waves become visible on the wings of the plane. The sudden visibility of sound just as sound ends is an apt instance of that great pattern of being that reveals new and opposite forms just as the earlier forms reach their peak performance. Mechanization was never so vividly fragmented or sequential as in the birth of the movies, the moment that translated us beyond mechanism into the world of growth and organic interrelation. The movie, by sheer speeding up the mechanical, carried us from the world of sequence and connections into the world of creative configuration and structure. The message of the movie medium is that of transition from lineal connections to configurations. It is the transition that produced the now quite correct observation: “If it works, it’s obsolete.” When electric speed further takes over from mechanical movie sequences, then the lines of force in structures and in media become loud and clear. We return to the inclusive form of the icon. -p12

The phenomenon of “peak performance” preceding “new and opposite forms” is similar to Engels idea of the Law of transformation of quantity into quality which roughly states that systems reach a point in quantity that abruptly changes their quality. A simple example is the change of water to steam by the quantity of heat applied. MM’s sound barrier phenomenon works similarly which he uses to talk about how the mechanical process of movie projection and filming creates an illusion of movement by applying a mechanical speed beyond simple comprehension. He anticipates that further advances in electronics (which could be seen as the proliferation of video that came soon after)will take film images further as shared cultural features.

While he doesn’t often cop to it, McLuhan’s theories often seem a lot like Marx and Engels’. The social determinism which M and E suss out the class mechanisms of the Industrial Revolution, are similar to the media determinism by which MM susses out the dynamics of the Information Age. I’ve gone into this is greater detail here.

Only now am I seeing that the Industrial and Information age, and indeed the works of M and E and MM could themselves represent this same quantity/quality law. That is, the dawn of the information age represents the point at which industrial speed becomes qualitatively different, moving decidedly from the precise and rapid movement of gears to the even more precise and more rapid movement of electrical pulses in a circuit. I’m somehow surprised that MM doesn’t just give us some jazzy line here like “breaking the information barrier.”

Its worth noting that in the mechanical process of editing and projecting film, the technicians of this must make a further leap toward accepting the illusion of the medium. On the other hand, contemporary producers of video can glide easily through the editing process with little knowledge or thought to the electronic processes that underpin their editing suites.

-

Capitalism as Dynasty

This idea suggests that:

American Democracy is discontinuous.

That is, 4 and 6 year election cycles create short lived regimes that can plan for broad reform, but lack the continuity to see it through. And while political parties create the possibility for continuity beyond election cycles they more often fail to achieve this continuity than not.

In discontinuity, ideological power is acqueisced to the power of capital

This happens

1 Because of spontaneous vacuums of power that are a consequence of the constant shifting of regimes.

2 Because capital is allowed into the function of elections.

3 Because with an absence of the possibility of a continuation of ideology, the continuous nature of the acquisition of wealth creates the possibility for long term planning.

Capital is the continuous political force

Because it can outlast regimes, and because though exerting influence it can have power over elections, capitalism (or the will of wealth to create more wealth) is the central dynasty(continuous power structure) of American Democracy

Thus, regimes who wish to curtail the power of capital fail not only because they lack political will or broad support, but because the discontinuity of ideological power makes this outcome far less possible.

-

UUM 010

For mechanization is achieved by fragmentation of any process and by putting the fragmented parts in a series. Yet, as David Hume showed in the eighteenth century, there is no principle of causality in a mere sequence. That one thing follows another accounts for nothing. Nothing follows from following, except change. So the greatest of all reversals occurred with electricity, that ended sequence by making things instant. With instant speed the causes of things began to emerge to awareness again, as they had not done with things in sequence and in concatenation accordingly. Instead of asking which came first, the chicken or the egg, it suddenly seemed that a chicken was an egg’s idea for getting more eggs.

There is a meta level irony in this paragraph that points to what is often a flaw, but many times an asset to MM’s writing. “That one thing follows another accounts for nothing,” could be taken as a criticism of the disjointed writing here. “So” in “So the greatest of all reversals” stretches the imagination of the ability of that word to connect that sentence with the previous. This all seems to be unrelated, or un-sequenced. However, what is being suggested here, and has been suggested earlier, is that human thought tends to take the form of external processes. In the mechanical age, people take the metaphor of thought as a mechanism, or about the nature of things in sequence. In the electronic age, where sequence is perhaps even more important, but sequences are so fast as to be hidden from view, people take the metaphor of thought to be a instant computation.

The supposed paradox of the chicken and the egg could actually be a consequence of sequential/mechanical thinking. To ask if the chicken came before the eggs is to assume a chicken came to this world fully formed. Of course, a chicken evolved from some other kind of bird which evolved from a reptile and so forth–all of which produced eggs. The answer is obviously: the egg came first. But thinking about a chicken mechanically, we think about it having a maker–similarly to thinking Adam was made from clay. Thinking about a chicken as an “egg’s idea” at least metaphorically, seems closer to the truth.

-

UUM 009

In accepting an honorary degree from the University of Notre Dame a few years ago, General David Sarnoff made this statement: “We are too prone to make technological instruments the scapegoats for the sins of those who wield them. The products of modern science are not in themselves good or bad; it is the way they are used that determines their value.” That is the voice of the current somnambulism. Suppose we were to say, “Apple pie is in itself neither good nor bad; it is the way it is used that determines its value.” Or, “The smallpox virus is in itself neither good nor bad; it is the way it is used that determines its value.” Again, “Firearms are in themselves neither good nor bad; it is the way they are used that determines their value.” That is, if the slugs reach the right people firearms are good. If the TV tube fires the right ammunition at the right people it is good. I am not being perverse. There is simply nothing in the Sarnoff statement that will bear scrutiny, for it ignores the nature of the medium.

Sarnoff’s address offers the sensible sounding antithesis to MM’s main point. Sarnoff, says “no, the message is the message” or argues that human will is paramount over the intrinsic wills of machine technologies. MM’s refutations here fall a little flat. In he case of firearms, the “its how you use them” has been a perennial favorite for gun owners and second amendment types. Seemingly this tired old arguments is starting to lose its luster, though it has seen a powerful and frightening reign.

The problem is that the “its how you use them” arguments sound sensible. Not only this, but they seem to champion human free will. Thus, they flatter a human sense of agency over the determinism. MM doesn’t attempt a hard-line argument for determinism (I think he is actually Catholic, which might have something to do with it), though his point is a somewhat deterministic one, it says that it isn’t human free will but the galvanizing nature of human encounters with technology which create history. His argument is that these technologies work on human lives and psyches in powerful and unseen ways. A clever McLuhanization of the old “its how you use them” line might be “its how they use you”.

-

UUM 008

The message of the electric light is like the message of electric power in industry, totally radical, pervasive, and decentralized. For electric light and power are separate from their uses, yet they eliminate time and space factors in human association exactly as do radio, telegraph, telephone, and TV, creating involvement in depth.

The most active passage here is the introduction of the “elimination of time and space factors in human association”. That is, because of the ability of these technologies to manipulate information that travels over wire or air at roughly the speed of light (without time lags that would render normal modes of communication impossible so long as you’re somewhere on Earth), they recreate the ability to communicate in depth in spite of geographical distance. This instantaneous nature of electricity is then what MM builds his theory of electronic tribalism upon. If advanced technologies allow us to create associations with far flung humans that are as rich in depth as a close-knit tribal alliance in direct proximity, we may find ourselves leaning into the relative comfort of that long-held pattern of association.

What is interesting for the present (2021) is that in the wake of the distancing required by the pandemic, this virtual or electronic world necessarily grows in scope and scale. As more and more communication is taken online, this virtual space is expanded while the metaphysical borders of the physical world of communication necessarily shrinks. Thus the message or effect of these forms of virtual communication forms are expanded and amplified. Socially, virtual forms of communication MEAN more.

With much being said about extreme political polarization, and the proliferation of conspiracy groups, these phenomenon appear as if they could be an outcome of the the twin effects of electronic tribalization, and the expansion of the virtual tribal space.

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.